This regional report will be updated each time fresh information is

available. It is published on the website in imperfect form because people need

information now.

In August, November and December 2001, as part of its community health

initiatives rather than a core function, Children of Fire assisted some elderly

residents of Joe Slovo squatter camp to get medical attention that they

urgently needed. Following work by volunteer nurse Lorraine Doyle in the camp,

it became clear that many people had severe eyesight problems. At the same time

there was a radio advertising campaign being aired about the Right to Sight

which gave the impression that treatment for poor people was free. This was not

the case. They were expected to find R50 for an initial assessment and R1500

for an operation. People living in squatter camps on R570 a month and paying

illegal landlords up to R200 a month rent, cannot possibly pay for treatment.

We also established that there would be a minimum of a year's wait for

cataract operations if people went to the geographically-closer Helen Joseph

Hospital (formerly called JG Strijdom). This seemed untenable for people barely

able to walk due to severely restricted vision.

Then we found that, near Soweto, Leratong Hospital's ophthalmic unit

could see a group of people from the squatter camp at end-August and that the

most urgent cases would then be operated on in November. One Zimbabwean doctor

working there had apparently carried out more than 1000 cataract operations

without payment, from the kindness of her heart. She seems to be one of too

many unsung heroes. Eight people from the squatter camp went in a bakkie to the

hospital for assessment. None could afford to contribute to the initial R200

transport cost. Some were subsequently referred elsewhere for spectacles or

medication; two were booked in for cataract removal in November.

Lydia (63) and Gabriel (85) went in for surgery on November 12th. On the

same day we also visited Ward 20, the burns unit, to meet all the paediatric

and adult patients.

Taking Lydia and Gabriel in to Leratong was a test of endurance because

of the lethargy of some civil servants. We at least thought ahead to provide

fizzy drinks for the two old people, but anyone seeking treatment in a state

hospital should take a "scarf tin" i.e. a lunch box, with them. We also took a

lot of magazines with us to share with the people in the queues because it is

so very boring sitting there hour upon hour. It would be a wonderful public

education opportunity to hand out health information booklets to people in

queues.

While one woman in the entrance lobby was wonderfully helpful - and, I

think, managed to fast-track the process a little, it still took an inordinate

amount of time to queue for a file; to then queue to see the ophthalmic nurse;

to then queue to see the doctor; to then queue to pay R52 for admission; to

then get the administator to understand that a cheque payment requires a

receipt in just the same way that cash does (this required a visit to the

superintendent's office); to then queue again for the doctor because she has

written the wrong date in the file even though the little blue card showed the

correct date, and to then sit and wait for a nurse to accompany people to the

ward. This all took about five hours.

In fact we abandoned the final step and went direct to the wards

ourselves. It was a long walk for Gabriel in particular but we managed to get

him a wheelchair for the final stretch.

Once we got to the wards, we wanted to be sure that Gabriel was in bed,

clean and comfortable, before we left him. While there seemed to be several

staff around, no one seemed very interested in helping.

A young man who had been in a car crash was lying on a stretcher,

seeming in some considerable pain. His drip was empty and we asked them to

attach a new one. When they then indicated that they would deal with him first,

it did not seem unreasonable - but the whole pace and lack of interest in most

new patients was unreasonable.

Gabriel looked exhausted, so in the end we established that one crumpled

bed was available for his use. I took off the dirty linen, went and found some

sheets and a sort-of pillow case, and made Gabriel's bed myself.

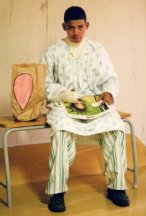

Lydia still had no bed six hours after she arrived at the hospital but

at least got a gown and sat on a chair waiting for someone else to leave the

women's ward so that she could move into their bed. There was no gown for

Gabriel while we were still there. And someone stole his bar of soap but we

brought him another to take home. Burns Unit

We were welcomed in the burns unit and presented gifts from a church in

Pretoria - mainly little decorated bags containing such items as toothpaste,

flannel, soap, toothbrush and for the children, including a toy and a little

book as well. Some of the books were written especially for children by the

children at St Mary's school, Bryanston. The details of this visit will appear

elsewhere on the website.

Other Hospitals

In all the waiting with Gabriel and Lydia, we had not been excessively

stressed, as we knew from experience that other state hospitals were worse by

comparison.

However a week or so later, when both returned for their checkups, a

further taste of idiotic bureaucracy seemed too much to bear. There was the

first queue for the files. One has to wonder why the files cannot be kept in

the unit where one is receiving treatment with just a memo card in the central

system to say that the file is with ophthalmics.

Then there was the very very long queue for ophthalmics. Gabriel and

Lydia were seen by the nurse and they thought that they were done for the day.

But no, they had to queue again to see the doctor.

After basic eye tests, she examined them more closely. Gabriel had not

had an artificial lens put in his eye under local anaesthetic because he was

not a "co-operative patient". After Lydia's description of the massive

injection into the eye area, we weren't so surprised. Gabriel was meant to wear

glasses but he couldn't get used to them and kept rubbing his left eye. The

doctor prescribed antibiotic cream as well as eye drops; she also prescribed

antibiotic drops and eye drops for Lydia - who was a "much easier patient".

Both will return in mid December, Gabriel to get laser treatment for the edges

of the old cataracts. Having seen the doctor it was now about 1pm, having

arrived in the hospital well before 8am.

Medical staff take tea breaks and lunch breaks - and there is no staff

overlap to keep the queue moving - and certainly no cup of tea for all the

tired sick people who just sit and sit and sit, staring at dull walls and dull

floors, the rhythmn of the day punctuated by intermittent coughs.

We were then sent somewhere else to get the appointment booked onto a

computer. It seemed illogical to have to join another queue just for that - the

doctor had the note of the appointment in her diary - why couldn't that be

transposed onto the computer at the end of the day? When we found the right

office, it was empty. No one knew if the woman would be back in five minutes or

an hour or ever. There was no written note.

Anticipating the worst, we split up. Gabriel and Lydia to wait there

with one Children of Fire volunteer; another to go to the dispensary in

anticipation of a queue there.

And what a queue there was. First job was to get a red sticker put on

the file and the file put in the box. There were 38 people in the room; a

further 43 sat or stood outside waiting; seven people were on crutches. There

was no system whereby simple medicines like eyedrops and common eyecreams could

be dispensed easily. Four members of staff were off sick or at meetings. A

similar number of extra jobs could usefully be advertised. Five people were

working, steadily enough. But it was not humane for the patients to have to

wait so long - hungry, tired and unwell.

The fat young woman with fake gold earrings, translucent orange blouse

and lime green trousers, sat there trying to look well off in her plastic

attire, and failing dismally. The round old woman stood nearby in her chequered

skirt, geometric red top and white beret. The next lady in a pink suit, glasses

and doek, looked ready for church. Another woman tried to sleep on the floor.

The tired drawn faces of everyone in the warm stale air of the hospital,

stared with the miserable patience of patients. The benches are hard, the faces

hopeless. Babies cry. Babies sleep. More babies cry. Peaked caps, floppy hats,

the cool dude in the yellow T-shirt and rastas, sporting the slogan "the chicks

dig me". The sick little girl lying on a bench and her father protectively

preventing anyone else from sitting near her. A torn lilac poster decorates the

walls. It says: Quality pharmacy care."

When we eventually see Annie Laxa the pharmacist, we suggested that

simple medicine like eye drops and creams could be given out by the doctor at

the time she sees the patient - not another three hours of waiting later.

Some people would probably even take up the option of paying for simple

medicines if they could save on the hours and hours of queueing. The man on

crutches who stood for so long just to get two bandages, painkillers and a

little pot of antiseptic solution, could surely have been dealt with by a

trainee nurse.

One woman described her day - arriving at the hospital at 6.35. Getting

a regular blood test at 7.45. Blood sent to the laboratory at 8.18 and back by

10.22. An X-ray followed. She got to the dispensary at 12 and finally got her

medicine at 14.55. She said: "I understand it takes time to test blood but why

do I have to spend a whole day here? Why does it take so so long to collect a

prescription."

There are hundreds of thousands of people who need jobs. There are

substantial funds for poverty alleviation that remain unspent. How hard can it

be to convert some of that cash into salaries for administrators who could be

taught to smile and handle files quickly and efficiently, and even spend it on

training more pharmacists and junior helpers?

The private sector doesn't make one talk to unfriendly unhelpful people

through dirty glass screens. The chairs are comfortable, the waiting time is

short, the rooms are light bright and breezy and one can even go and have a cup

of tea at a cafe-type table nearby.

There seem to be employment opportunities in abundance that would cut

the queues at Leratong and lift the spirits of everyone sitting there waiting,

waiting, waiting.